Semaj Brown at the FIA a poet, a priestess, a force of nature borne of anger and love

By Jan Worth-Nelson

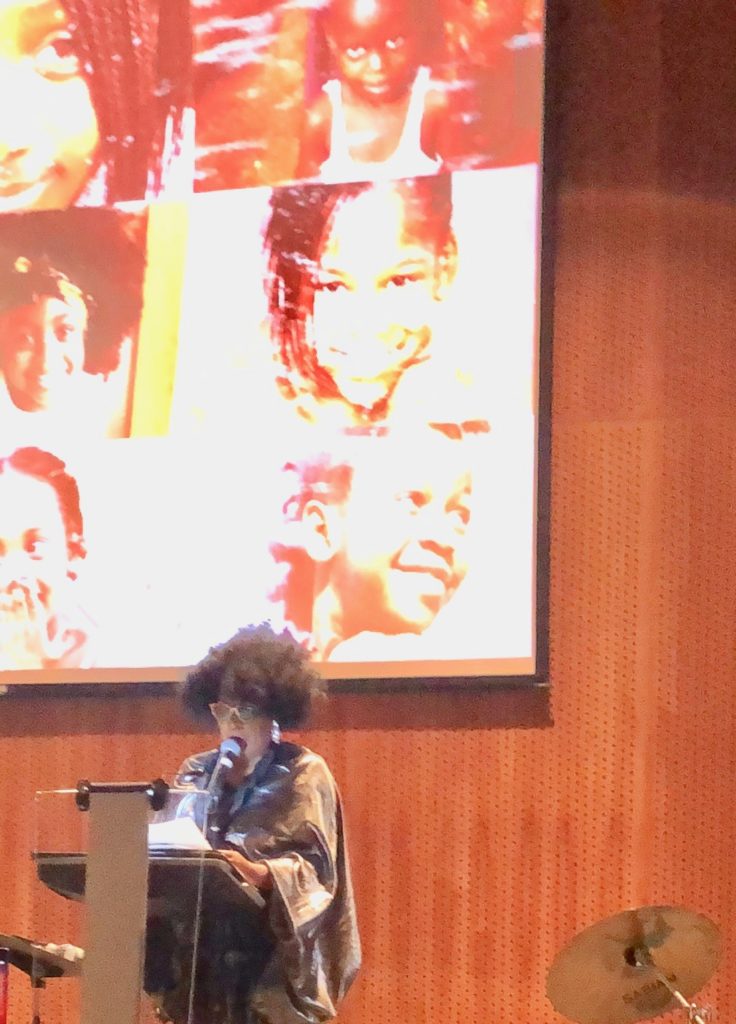

In the opening of Semaj Brown’s Jan. 26 performance at the Flint Institute of Arts, FIA director John Henry described Brown, Flint’s first poet laureate, as a “science-driven author, dramatist, playwright, and educator who builds inter-disciplinary curriculum.”

And since Brown’s appointment as poet laureate by former Mayor Karen Weaver last year, she has plunged with high-octane commitment, launching literacy programs throughout the city, corralling four Flint churches and a number of schools to offer reading to children and opportunities to write, love and learn from poetry.

As he concluded the intro, Henry promised the standing-room-only audience in the FIA’s Isabel Hall, in a radical understatement, that “you are in for a show.”

Indeed, after the spell-binding 90-minute performance, it became clear that in addition to the blue ribbon resume credentials John Henry cited, there is something more. Brown is a poet undeniably. But she also is a priestess, a force of nature, and a phenomenon borne of anger and love.

Brown had been commissioned by the FIA to create performances around two works of art in the FIA collection. The first was Epoch, a tableaux of an African-American soldier of World War I, created from an old photo, by contemporary painter Whitfield Lovell. The painting is viewable here on the FIA website.

Brown titled her piece “Something Called War.”

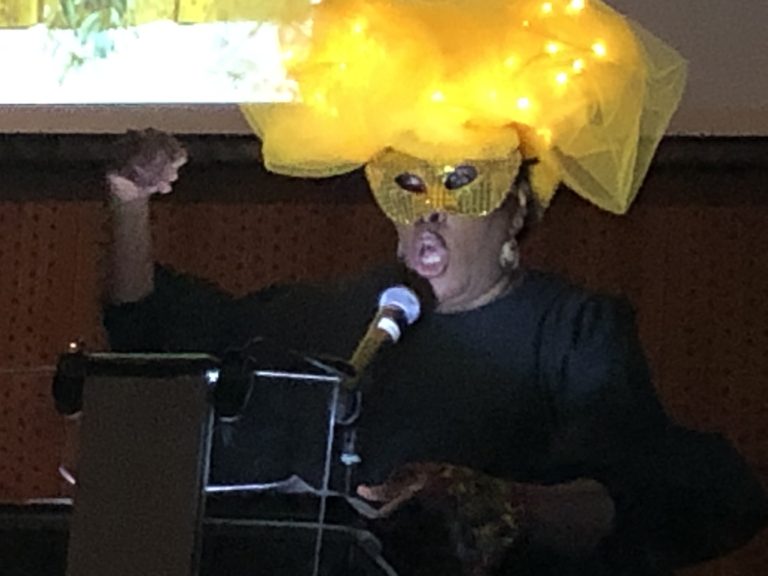

Surely the audience could not have expected a more startling and original response. Brown advanced slowly from the back of the room with Billie Scott Lindo, artistic director of the New McCree Theatre. Their heads were adorned with otherworldly piles of netting and lights, like frothy external brains (made by Rosie Ray Henderson) their faces obscured by glittery masks.

In a mechanical, repetitive robot’s voice, Brown spoke as “Beyond Consciousness,” (BC) an authority on “Moronic Humanoid Studies” from “The Year 10,000 Post Earth.” As she delivered her “lecture,” Lindo, as “Lingering Humanoid Consciousness,” (LHC) asked questions in a singsong childlike voice and sang intermittent incongruous snippets of “If You’re Happy and You Know It Clap Your Hands.”

While the premise risked slipping into farce, Brown in fact pulled it off, delivering a gripping and heart-wrenching commentary. The robot flat voice combined with the child’s poignant, perplexed questions to create a damning dirge encompassing race, war, lynching, the extinction of the planet. And the treatise concluded that “Moronic Humanoids” ultimately were doomed by their failure to “develop compassionate technology of heart and soul.”

Here are a few excerpts from that remarkable piece — reduced only to words on the screen, but worth capturing, at least to offer a sense of the work.

Beyond Consciousness (BC) begins by saying that the “Moronic Humanoids” were “once thought to be mythological” but with the discovery of the painting, “now we have proof of their existence.

“We will answer the question, ” BC says, “what happened to Earth?

BC notes the “Petrified soldier in dehydration of history, corpse upright, initiated by dry dignity, by grief bouquet,” his posture suggesting “he was sentenced to kill, imprinted ghost on timeworn timber plank,” a posture “consistent with other vertical death formalities.

“That was “something-something-something called lynching-lynching-lynching…dangling blood from elongated oxygenated producers– or trees.”

“Trees! Trees! ” the LHC exclaims, lapsing into nerve-wracking snippets of “If you’re happy…”

“Truth: Moronic Humanoids worshipped trees, therefore they hung death from them,” BC replies.

“What contributed to Moronic Humanoids’ extinction?” LHC eventually asks.

“The major contributor…was segregating into something called race-race-race,” BC replies.

LHC asks, “What is something-called-race?”

“Not-sure-not-sure, scientists are still researching,” BC answers. “Theory: race is a hallucination, [laughter from the audience]…A symptom of — Moronic Humanoid Psychosis — statistically negligible diversity hue in skin, something called melanin…”

Further and finally, in an urgent rush of duet with her childlike partner, BC says, it has been determined that:

“the Moronic Humanoids engaged in the act of something called war..war…war..indicates a terminal dysfunction. What is something called war? if you’re happy and you know it……extreme killing compulsion, deadly syndrome organized around hallucinations of power fostered by Moronic Humanoid Psychosis, from which they suffer greatly.

“Their aversion to life was so fierce, so perverse, it extended to the demolition of their cousins, air, water, entire planet…Moronic Humanoids lynched the planet.”

And finally, the punchline. BC continues, “They organized advanced technologies outside of themselves, to advance society, while neglecting the ultimate technology of heart and soul and internal capacity to even love and receive love.”

“Questioning, questioning..” the LHC pleads, “Did not Moronic Humanoids develop compassionate technology of heart and soul?

“It is confirmed,” BC replies, “They did not develop compassionate technology of heart and soul. Correct.”

And so the piece fades out with a robotic repeat, as if the robot herself has malfunctioned, If you’re happy…and you’re happy..happy..if you’re happy..if you know it…if you’re happy…”

After this piece, Brown came back as “herself” and shared with the audience some of the etiology of her work, describing her childhood as the daughter of Detroit activist and scholar Bessie James — a powerful, demanding, and fiercely loving woman who made Semaj practice classical violin five hours a day but let her and her sister roam the halls and galleries of the Detroit Institute of Arts at will.

She delivered her second piece, “Marie Laveau” based on a color pencil drawing lithograph of 19th Century voodoo priestess Marie Laveau by American artist Renee Stout–a work purchased in 2013 by the FIA. Along with that searing piece, she offered the poem “R.O.A.R” — an audience favorite in which girls are taught alternative rhymes of empowerment and protection to use when jumping rope.

Brown’s husband, James Brown, a family physician who collaborates with her on many performances, concluded the program with “Freedom Tree Song,” a solo on his famous “arborlune,” an instrument he makes and strings himself from back yard dropdown. Together in the last piece they were very loud–let’s call it cathartic, a primal scream.

Brown told me once that she thinks she was injected somewhere along the line with “anger serum.”

“And yet I’m happy,” she said that time. While she is formidable–larger than life with that powerful voice–her exuberance, redeeming intelligence, regenerative humor, truth telling and irrepressible sense of language and sound, allow a listener to open up widely to the work. It’s a combination that makes her performances unforgettable, uncomfortable, a bit scary, lovable, and wholly significant.

Semaj Brown’s latest book is Bleeding Fire: Tap the Eternal Spring of Regenerative Light, which came out in 2019 from Broadside Lotus Press. The performance at the FIA launched an FIA exhibit called “Community,” running through April 19 and celebrating works by African American artists in the FIA collection.

More information is available about the current FIA show at https://flintarts.org/events/exhibitions/community.

More information about Semaj Brown is available at https://poets.org/poet/semaj-brown and at several previous East Village Magazine pieces, for example here and here.

Banner photo: Backdrop from the FIA performance (Photo by Jan Worth-Nelson).

EVM Editor Jan Worth-Nelson can be reached at janworth1118@gmail.com.